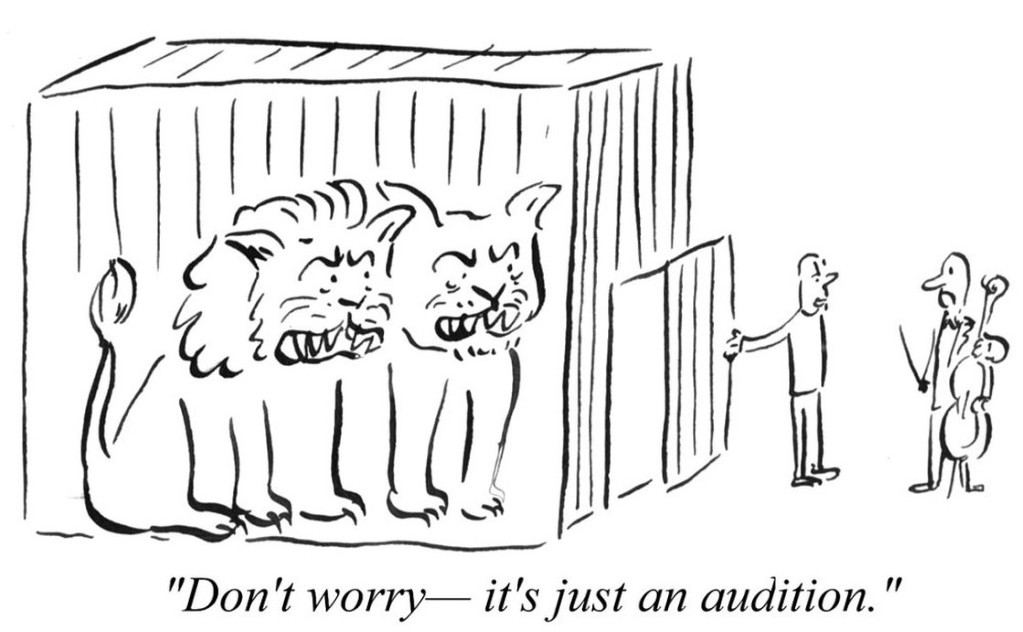

A stage, a bunch of people listening to you, and ten minutes to show how much you worth: it’s the classic audition, a “make-or-break” occasion when if you do a mistake you can’t fix it. Bogey to some, foolproof method to others: in many cases a “depersonalized” test, with the musician hidden by a curtain: it happens in symphony orchestras auditions in which they try to ward off the risk of likes and recommendations giving to every candidates the “privilege” of anonymity.

As Los Angeles Times writes, the way to select musicians for orchestral job has been changing over time: there “were the heady days when the term “maestro” conferred dictator status, when the likes of George Szell and Arturo Toscanini reigned.” At that time, “to gain entry to a major classical orchestra — say, the New York Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony — used to depend mostly on pleasing the music director.”

Then, more relaxed manners came: in the early ’70s, as says David Taylor, assistant concertmaster of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, “a player then was chosen first and foremost for his artistry, his quality of musicianship — even if he dropped a note here or there.” Furthermore, according to L.A. Times, “less critical atmosphere was also a boon to career musicians who could, according to L.A. Philharmonic principal bass Dennis Trembly, ‘simply be invited to the music director’s hotel room, perform a piece of music and get a handshake.’”

In late ’70s “the process tightened because unions exercised great scrutiny and orchestras needed to show objectivity in their choices to avoid litigation.” All big symphonic orchestras have protocols, procedures, selection committees and sub-committees, with many rounds to pass until a job offer. So, the more orchestras try to be fair, the more complex and rule-bound it gets. After all, it is also a matter of numbers: how they can evaluate hundreds of candidates without auditions? However, some cultural values still differentiate European from American orchestras. Carrie Dennis, currently principal violist of the L.A. Philharmonic, says auditioning for Berliner was “pretty civilized. You don’t play this or that snippet. If you get to the second round you play a concerto — on the stage, in a hall, with all musicians in the audience.”

And what about baroque orchestras world? As often happens, small is better. As Alfredo Bernardini told us in his interview, is quite common in early music ensembles testing a candidate in some concerts before offering him a job. And Theresia Youth Baroque Orchestra? We have been recruiting in the classic manner for three years, but this year our Artistic Director Mario Martinoli decided “to change and to set hearings as a training opportunity more than the classic make it or brake it moment. Candidates will work for three days with the three principal TYBO’s conductors: they will rehearsal in chamber groups and in orchestra, with a double benefit: for us, the possibility to know their attitude to team work besides their technical ability; for them, the occasion to meet and work with three great Maestros such as Claudio Astronio, Alfredo Bernardini and Chiara Banchini. Furthermore, we are planning some seminar with renowned musicologists thank to the collaboration of Fondazione Cini.”.