Everything you wanted to know about

gut strings, but were afraid to ask

By Léna Ruisz

November 15, 2022

Read the post in German

Read the post in Hungarian

When a curious violinist begins to explore historical performance practice, gut strings are one of the first topics to come up. Before the era of metal strings, musicians used a material that may surprise the uninitiated: as early as the Egyptian Dynasty, strings were made with intestines from sheep, cattle or other animals. The first violins and their predecessors bore four pure gut strings; it was not until the end of the 16th century that the G strings were wound with silver or copper wire to produce a richer, more resonant sound. The arrangement with one wound and three pure gut strings remained standard for a long time, until about three centuries later, when the technology for making a sufficiently thin wire to wind the D string was invented. The A-string was the last of the four strings to be changed from pure to wound gut – Pirastro developed the first wound aluminium gut A-string in 1951. Because of their thin gauge, gut E strings were never wound, and pure gut strings were used well into the twentieth century. The appearance of the first steel E-string is dated to around 1910, but it only became popular after the Second World War, when sheep gut started to be in short supply.

Choosing the right strings for the instrument requires a lot of experimentation and highly probable E-string snap in the face when playing, but the reward is great – a sweet, vibrant sound favoured by great artists like Pablo Casals and Kreisler. If you think of Eugene Ysaÿe‘s solo sonatas for violin for instance, you may want to bear in mind that he was the last world-famous violinist to play on gut E, A and D strings throughout his active career. Even Jascha Heifetz, one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, claimed that the only way to produce a truly personal sound on the violin was to use gut strings – or at least a mixture of them; he chose a silver wound gut G string, an unwound D and A string and a steel E string. Just imagine, all the great violin concertos, like the ones by Mendelssohn, Beethoven and Brahms, were written for gut strings!

However, they come at a price – they are much more “alive” than their metal colleagues; one has to get to know them very well to achieve the “sweet and personal sound” mentioned above. For that reason, let us now discuss some of the most fundamental questions on this topic!

How should I store them?

The arch-enemy of gut string is humidity. Be sure to keep them in an airtight place – the original plastic packaging in the pocket of the violin case is a great choice.

How to take care of my strings?

Properly stored gut strings require no special care. However, if the weather is exceptionally dry, a few drops of almond or olive oil applied to the strings overnight can make a big difference in avoiding the annoying buzzing and whistling that such conditions often cause. I always carry a small bottle of oil with me, just in case.

Should I pre-stretch them?

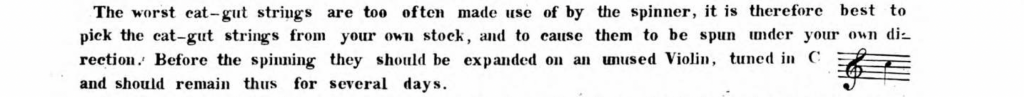

Speaking from experience, a used or properly pre-stretched string can prove very useful in the event of a string emergency. Spohr suggests in chapter 3 of his Violinschule (1833) to stretch the upper three strings on a spare violin by winding them slowly up to the note C5 and leaving them overnight. This method has worked wonderfully for me; with a slight modification on the top string – I tune it to D5 instead.

There are tiny frays on the string — what to do with it?

On the E string, there is a possibility that they may predict a string snap, but in general they are not a reason to be worried. However, it is advisable to trim them with a small pair of hand scissors or nail clippers so that the fingers do not make them bigger. Frequent oiling of the strings can prevent this from happening. If string breaks are suspiciously frequent, it’s worth checking the tiny (often bone) part between the fingerboard and the peg box; sometimes a small but sharp edge of the top nut can weaken or cut the strings.

Any special care while tuning?

Yes! The baroque violin (or classical violin) has no fine tuners, so all adjustments must be made with the pegs. This can mean extra tension and more movement – before you put on a new string, take a 2B pin and rub the groove on the bridge and also the groove leading into the pegbox. This ensures that the string can move freely without pulling the bridge to an angle that could cause the violin to break if it falls. Check the angle and position of the bridge frequently!

How do I put up a new string?

During our last workshop with the Theresa Ambassadresses, we decided to make a video about it – watch it on our YouTube channel and let us know if you found it useful!

Alles, was du schon immer über Darmsaiten wissen wolltest, aber nie zu fragen gewagt hast

Wenn neugierige Violinisten anfangen, sich mit historischer Aufführungspraxis zu beschäftigen, ist das Thema der Darmsaiten eines der ersten Themen, dem sie begegnen.

Vor der Entwicklung der Metallsaiten verwendeten Musiker ein Material, das die Neulinge überraschen könnte: schon in der ägyptischen Dynastie wurden Saiten aus Därmen von Schafen, Rindern oder anderen Tieren hergestellt. Die ersten Geigen und ihre Vorgänger waren mit vier Darmsaiten besetzt; erst gegen Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts wurden die G-Saiten mit Silber- oder Kupferdraht umsponnen, um einen reicheren, volleren Klang zu produzieren. Die Kombination aus einer umsponnenen und drei reinen Darmsaiten blieb lange Zeit Standard, bis etwa drei Jahrhunderte später die Technik zur Herstellung eines ausreichend dünnen Drahtes zum Umspannen der D-Saite erfunden wurde. Die A-Saite war die letzte der vier Saiten, die von der reinen auf die umsponnene Darmsaite umgestellt wurde – Pirastro entwickelte 1951 die erste umsponnene Darm-A-Saite mit Aluminium. Wegen ihrer geringen Stärke wurden E-Darmsaiten nie umgewickelt, und reine Darmsaiten wurden bis weit ins zwanzigste Jahrhundert hinein verwendet. Das Erscheinen der ersten E-Saite aus Stahl wird auf etwa 1910 datiert, aber sie wurde erst nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg populär, als Schafsdarm Mangelware war.

Die richtigen Saiten für das Instrument zu finden, erfordert viel Experimentieren, aber die Mühe lohnt sich – ein strahlender, lebendiger Klang, der von großen Künstlern wie Pablo Casals und Kreisler bevorzugt wurde. Wenn du zum Beispiel an Ysaÿes Solosonaten für Violine denkst, fällt dir vielleicht ein, dass er der letzte weltberühmte Geiger war, der während seiner gesamten aktiven Karriere auf E-, A- und D-Saiten aus Darm spielte. Selbst Jascha Heifetz, einer der einflussreichsten Musiker des 20. Jahrhunderts, war auch der Meinung, dass die einzige Art und Weise, einen wirklich persönlichen Klang auf der Geige zu erzeugen, der Verwendung von Darmsaiten bedarf – oder zumindest in einer Mischung davon; er wählte eine silberumsponnene Darm-G-Saite, eine unumsponnene D- und A-Saite und eine E-Saite aus Stahl. Stell dir vor, alle großen Violinkonzerte, wie die von Mendelssohn, Beethoven und Brahms, wurden für Darmsaiten geschrieben!

Sie haben jedoch ihren Preis – sie sind viel “lebhafter” als ihre Kollegen aus Metall; man muss sie sehr gut kennen lernen, um den oben erwähnten “strahlender, lebendiger Klang” zu erreichen. Kommen wir deshalb nun zu einigen der grundlegendsten Fragen zu diesem Thema!

Wie sollte ich sie aufbewahren?

Der Hauptfeind der Darmsaiten ist die Feuchtigkeit. Bewahre sie unbedingt an einem luftdichten Ort auf – die Original-Plastikverpackung in der Tasche des Geigenkastens ist eine gute Wahl.

Wie soll ich meine Saiten pflegen?

Richtig gelagerte Darmsaiten benötigen keine besondere Pflege. Wenn das Wetter allerdings außergewöhnlich trocken ist, können ein paar Tropfen Mandel- oder Olivenöl, die über Nacht auf die Saiten aufgetragen werden, einen großen Unterschied machen, um das lästige Schnarren und Pfeifen zu vermeiden, das unter solchen Bedingungen oft vorkommt. Ich habe immer ein kleines Fläschchen Öl bei mir, nur für den Fall.

Sollte ich die Saiten vorspannen?

Ich spreche aus Erfahrung, dass sich eine gebrauchte oder richtig vorgedehnte Saite im Falle eines Saitennotfalls als sehr nützlich erweisen kann. Spohr schlägt in seiner Violinschule (1833) vor, Saiten auf einer Ersatzgeige zu spannen, indem man sie langsam bis zum Ton C aufzieht und über Nacht liegen lässt. Ich habe diese Methode für die beiden oberen Saiten erfolgreich angewendet.

Die Saite hat winzige Fransen – was ist damit zu tun?

Bei der E-Saite besteht die Möglichkeit, dass sie einen Saitenriss vorhersagen, aber im Allgemeinen sind sie kein Grund zur Panik. Es ist jedoch empfehlenswert, sie mit einer kleinen Handschere oder einem Nagelknipser zu kürzen, damit die Finger sie nicht vergrößern. Häufiges Einölen der Saiten kann dies vermeiden.

Gibt es Besonderheiten beim Stimmen?

Ja! Die Barockgeige (oder klassische Geige) hat keine Feinstimmer, daher müssen alle Korrekturen mit den Wirbeln gemacht werden. Bevor du eine neue Saite aufziehst, nimm einen 2B-Stift und reibe die Rille am Steg und auch die Rille, die in den Wirbelkasten führt ein. Dadurch wird sichergestellt, dass sich die Saite frei bewegen kann, ohne den Steg in einen Winkel zu ziehen, der bei einem Sturz zum Bruch der Geige führen könnte. Überprüfe den Winkel und die Position des Steges regelmäßig!

Wie ziehe ich überhaupt eine neue Saite auf?

Während unseres letzten Workshops mit den Theresa-Ambasadresses haben wir entschieden, ein Video darüber zu machen – schau es dir auf unserem YouTube-Kanal an und lass uns wissen, ob es hilfreich für dich war!

Minden, amit tudni akartál a bélhúrokról, de féltél megkérdezni

Amikor egy kíváncsi zenész elkezdi felfedezni a historikus előadási gyakorlatot, a bélhúrok helyes használata egy fontos téma, ami szóba kerül – az egyik első nagy különbség a modern és barokk hangszerek között.

A fémhúrok korszaka előtt a zenészek olyan anyagot használtak, amely meglepheti a beavatatlanokat: már az egyiptomi dinasztia idején birkák, szarvasmarhák vagy más állatok beleiből készítettek húrokat. Az első hegedűk és elődeik négy nyers bélhúrral rendelkeztek; csak a 16. század végén kezdték a G húrokat ezüst- vagy rézhuzallal megfonni, a gazdagabb, felhangdúsabb hangzás érdekében. Az egy fonott (G) és három tiszta bélhúr (D-A-E) kombinációja egészen három évszázaddal későbbig szabványos maradt; ekkor találták fel a D húr fonásához elegendő vékonyságú huzal előállításának technológiáját. Az A-húr volt az utolsó a négy húr közül, amelyet nyers bélhúrról fonott bélhúrra cseréltek – Pirastro 1951-ben fejlesztette ki az első fonott alumínium-bél A-húrt. A vékonyságuk miatt a bélből készült E-húrokat soha nem fonták, és a nyers bélhúrokat egészen a huszadik századig használták. Az első fém E-húr megjelenése 1910 körülre tehető, de csak a második világháború után vált népszerűvé, amikor a birkabélből hiánycikk lett.

A megfelelő húr kiválasztása a hangszerhez sok kísérletezést igényel, de nagyon megéri – sokszínű, egyéni hang lesz a fáradozás jutalma, amelyet olyan nagy művészek kedveltek, mint Pablo Casals vagy Fritz Kreisler. De gondolhatunk akár például Ysaÿe hegedűre írt szólószonátáira is; érdemes észben tartani, hogy ő volt az utolsó világhírű hegedűművész, aki aktív pályafutása során végig bélből készült E-, A- és D-húrokon játszott. Még Jascha Heifetz, a 20. század egyik legjelentősebb zenésze is azt állította, hogy a hangszeren csak úgy lehet igazán személyes hangzást elérni hogyha bélhúrokat használunk – vagy legalábbis ezek keverékét; ő ezüsttel fonott G-bélhúrt, és fonatlan D és A húrt, valamint egy fém E-húrt választott. Szédületes elképzelni, hogy az összes nagy hegedűversenyt, például Mendelssohn, Beethoven és Brahms hegedűversenyeit bélhúrokra írták!

Ennek azonban ára van – a bélhúrok anyagukból adódóan “élettelibbek” mint fémből készült társaik; nagyon jól meg kell ismerni őket ahhoz, hogy elérjük a fent említett sokszínű és személyes hangzást. Álljon tehát itt pár alapvető kérdés a témában!

Hogyan tároljam a húrjaimat?

A bélhúrok ősellensége a nedvesség és a pára. Mindenképpen tartsuk őket légmentesen zárva – az eredeti műanyag csomagolás a hegedűtok zsebében kiváló választás.

Hogyan gondoskodjak a húrokról?

A normál körülmények között tárolt húroknak nincs szükségük extra törődésre – kivéve, ha játék közben sípolni kezdenek a túl száraz levegő miatt; ebben az esetben néhány csepp olíva- vagy mandulaolaj jól jöhet. Én mindig tartok magamnál egy kis üvegcsét az ilyen esetekre; egy éjszakai olajfürdő a húrokon csodákra képes.

Érdemes bejátszani őket előre, akár még használat előtt?

Tapasztalatból mondom; egy előre bejátszott húr nagyon jó szolgálatot tud tenni egy vészhelyzetben. (mindenkinek van legalább egy hajmeresztő húrszakadás-története…) Louis Spohr, a 19. század egyik legjelentősebb tanár-zeneszerző-hegedűművésze 1833-ban írt Hegedűiskolája harmadik fejezetében ad egy érdekes tanácsot; egy használaton kívüli hangszeren érdemes a nyers bélhúrokat (tehát a D-, A-, E-húrokat) az egyvonalas C-hangra felhangolni, és éjszakára otthagyni. Ez a módszer nálam bevált; egy kis módosítással a felső húr esetében – én az E-húrt az egyvonalas D-re hangolom.

Pici foszlányok/szálak vannak a húron. Aggódjak?

Ha az E-húr kezd foszlani – talán. Sokszor egy hirtelen szakadást jeleznek ezek az apró szálak, főleg, ha direkt a vonó alatt, vagy a fogólap sokszor használt részén jelennek meg. Hogy ne szaladjanak tovább, egy körömolló vagy körömcsipesz segítségével érdemes lecsippenteni őket. A húrok gyakori olajozása megelőzheti ezt a problémát. Ha gyanúsan sokszor szakadnak a húrok, érdemes megvizsgálni a fogólap és a kulcstartó közötti pici (sokszor csont) részt, a nyerget; néha egy itt kilógó apró, de éles él gyengíti vagy vágja el a húrokat.

Mire figyeljek, ha hangolok?

A barokk (és klasszikus) hangszereknek nincsenek finomhangolói; csak a kulcsokat tudjuk használni. Ez veszélyes tud lenni az extra feszültség és nagyobb mozgástér miatt – fontos a hídon és a nyeregnél lévő barázdát alaposan begrafitozni egy minimum 2B-s ceruzával – így jobban fog csúszni a húr, és nem fogja magával húzni a hidat. Érdemes gyakran ellenőrizni a híd dőlésszögét és helyzetét, mert egy lecsapódó híd akár be is törheti a hegedű fedőlapját!

Tippek egy új húr felrakásához?

A legutóbbi Theresia-Workshopon úgy döntöttünk Anna-val és Luca-val, hogy készítünk erről egy videót – a YouTube-csatornánkon meg is nézheted – reméljük, hasznosnak találod!