What is genius? And what in particular is “the French musical genius”? According to Claude Debussy it is “clarity, elegance and simple and natural declamation: french music above all wants to give pleasure.” It’s not unlike that Debussy was thinking about Rameau while saying this words: in fact Debussy absolutely adored Rameau, and felt he represented the French tradition at its peak. He loved Rameau’s “delicate and charming tenderness… without that German affectation of profundity, without the need to underline or explain everything”. According to Debussy “the huge Rameau’s contribution was being able to discover the “sensitivity in the harmony”; he could sort out some colours, some shades which earlier composers just had a faint idea of”. And we know how strong was this admiration also because Debussy himself wrote an immortal piano piece devoted to Rameau: “Hommage a Rameau”, from Images first book.

Debussy used to complain about the general ingnorance of Rameau’s music, as well as of other French Baroque composers: “Why so much lack of interest for our great Rameau? For Destouchs, which is almost unknown? For Couperin, poet of the harpsichord? This disregard is shameful, because it lets other countries – so proud of thier glories – think that we do not care ours.” At the time of Debussy, it was usual to complain that French composers were understimated: it was one aspect of nationalistic ideas, but sure with a part of truth, especially in the knowledge of baroque and classic composers. As a matter of fact, we had to wait till the 80s of 20th century for a complete rediscovery of Rameau’s music – and not only Rameau’s – thanks to musical philology, performances on early instruments and passionate researches by musicians fond of baroque music.

At a first glance modern listeners, even if they love Rameau, may disagree with Debussy’s words about clarity, elegance and simpleness: as Ivan Hewett writes on The Telegraph “for many Rameau is the opposite of natural, clear and charming. He embodies the strangeness of the French mid-18th century aristocratic culture that nurtured him. For exotic extravagance and studied formality this has probably never been equalled. Rameau’s melodies can seem like a room at Versailles, so encrusted with ornamental curlicues and flourishes that you lose sight of what’s underneath.”

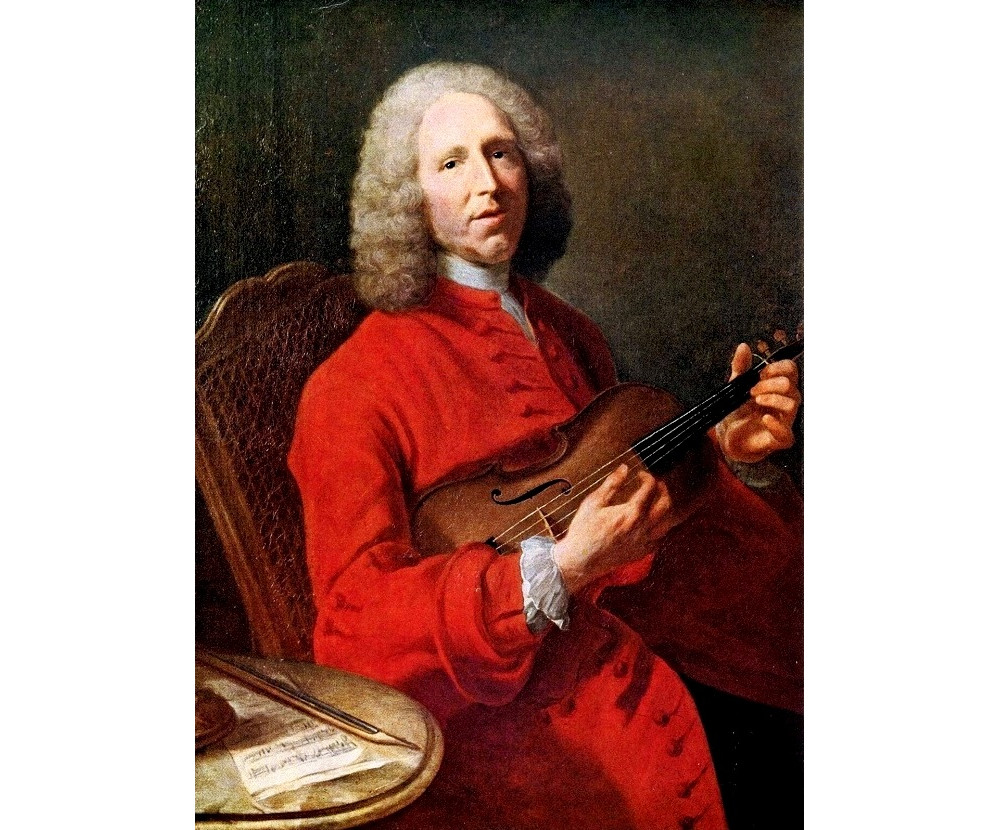

Nowadays we admire Rameau as a genius for the complexity of his musical identity: Rameau’s music is characterised by the exceptional technical knowledge of a composer who wanted above all to be renowned as a theorist of the art. Nevertheless, it is not solely addressed to the intelligence, and Rameau himself claimed, “I try to conceal art with art.” The paradox of this music was that it was new, using techniques never known before, but it took place within the framework of old-fashioned forms. Rameau appeared revolutionary to the Lullyistes, disturbed by the complex harmony of his music; and reactionary to the “philosophes,” who only paid attention to its content and who either would not or could not listen to the sound it made. The incomprehension he received from his contemporaries stopped Rameau from repeating such daring experiments as the second Trio des Parques in Hippolyte et Aricie, which he was forced to remove after a handful of performances because the singers had been either unable or unwilling to render it correctly.

Throughout his life, music was his consuming passion. It occupied his entire thinking; Philippe Beaussant calls him a monomaniac. It was said “His heart and soul were in his harpsichord; once he had shut its lid, there was no one home.” The details of Rameau’s life are generally obscure, especially concerning his first forty years, before he moved to Paris for good. Born in 1683, he was a secretive man, and even his wife knew nothing of his early life, which explains the scarcity of biographical information available. One can’t believe that it was not until he was approaching 50 that Rameau decided to embark on the operatic career on which his fame as a composer mainly rests. He lived with his wife and two of his children in his large suite of rooms in Rue des Bons-Enfants, which he would leave every day, lost in thought, to take a solitary walk in the nearby gardens of the Palais-Royal or the Tuileries. Sometimes he would meet the young writer Chabanon, who noted some of Rameau’s disillusioned confidential remarks: “Day by day, I’m acquiring more good taste, but I no longer have any genius” and “The imagination is worn out in my old head; it’s not wise at this age wanting to practise arts that are nothing but imagination.” In spite of this discouragement, Rameau pursued his activities as a theorist and composer until his death (1764), leaving us the legacy of one of the most impressive musical heritages.

Theresia Youth Baroque Orchestra will perform excerpts from Rameau’s “Zoroaster” in the next concerts, on 14th October in Lodi and on 16th and 17th October in Rimini. Find out more informations here.